Written by Zoë Karl-Waithaka, Managing Director and Partner, BCG Nairobi

According to research released by Oxfam in 2023, seven people across Ethiopia, Kenya, Somalia and South Sudan will die of hunger-related causes in the time it takes the average reader to complete this article.

It is imperative that all stakeholders in the food and agriculture sectors recognise that there can no longer be a “business as usual” approach. Something has to change, and quickly.

Zoë Karl-Waithaka, Managing Director and Partner, BCG Nairobi

SOS Sahel’s Africa Days Forum taking place on 27th and 28th June 2024 in Senegal will this year be focused on “Lost Crops, New Opportunities: Securing our Future with the Crops of the Past” and is expected to be a key forum for introducing new ideas to tackle this challenge.

Although Africa’s population has doubled in the last 30 years, food production has not kept pace with yields often below the global average. Africa has 65% of the world’s arable uncultivated land, varied agricultural environments and rich plant life that make it possible to develop sustainable food systems. Indigenous communities in Africa have long used local crops for food, medicine, and decoration. However, these native crops are being replaced by varieties preferred by industrial agriculture like maize, rice, and wheat. Widespread planting of these crops has driven uniformity of diets and led to the neglect of other crops, which we now refer to as “orphan crops”.

An “orphan crop” (often categorised with, or referred to as “lost crop”, “neglected crop” or “forgotten crop”) is a plant species that is important for food security, nutrition, and livelihoods in certain regions but receives little attention from agricultural research, development, and policy efforts on a global scale. However, such crops are often very adaptive and resilient – with ability to grow in marginal lands with low amounts of inputs. Examples of these include millets and sorghum.

Recognised in 2023 by the United Nations as “The year of the Millet” – millets are contextualised as “Super Foods” because of their highly nutritious properties including magnesium, manganese, phosphorus, zinc, selenium, copper and iron. They have further benefits as they typically utilise less water and grow in less time than many other grain-based products.

So why have millets been ignored, or more aptly – forgotten, until now? The challenge is two-fold. Firstly, there is a case of a weak value chain – traditional wheat and grain-based products have well established ecosystems which start at the farm and end in the form of a packaged product in supermarkets.

Second, related to the above, investments in conventional crops is significantly higher than in orphan crops. Conventional crops benefit from extensive global research networks, funding, and technological innovations, including genetic modification and precision agriculture, enhancing their productivity and market appeal.

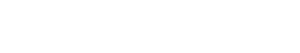

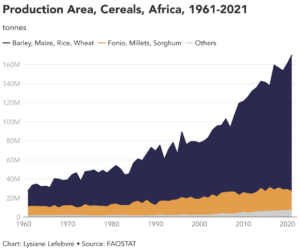

The following two charts tell an interesting story.

The first is research from the Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations (FAO) which highlights the priority areas for production of cereals in Africa. It is clear that investment and focus is on conventional crops such as maize, rice, wheat and barley (with more than 40% of our calories coming from the first three crops).

The second chart is derived from a report by the Export-Import Bank of India (Eximbank) and highlights that despite modest improvements in global yields of millets, the area under harvest has been declining steadily over time.

Given the challenges posed by climate change and the strong nutritional qualities of many orphan crops, the concept of revisiting these food sources is gathering momentum and is not simply isolated to Africa. For example, newly re-elected Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi has been a key driver of promoting this shift in food systems and has initiated various initiatives and campaigns to enable this. However, to translate these efforts into large scale uptake in our food systems globally, we will need consumers to create demand for these products, and food companies to invest in product formulation and technologies that enhance processing. Importantly, we will also need enough seeds to grow these crops and investment in R&D to promote higher yielding varietals.

While “Orphan crops” are now being championed as “Opportunity Crops” by Dr. Cary Fowler – the U.S. Special Envoy for Global Food Security, perhaps we should term them as “Wonder crops” for all the wonderful qualities they possess. These crops not only serve as sources of dietary diversity but also as cornerstones of cultural identity and heritage and with their nutrient dense, hardy qualities provide a potential solution to feed growing populations in continually harshening growing conditions.

We need to look beyond the current commercialised conventional crops and take the necessary steps to unlock this opportunity.

Photos supplied.

Relevant Agribook pages include “Indigenous food crops” and “Sorghum“.